A reading log for March, April and May 2024. If so inspired, you can find me on Goodreads.

Stats:

- 8/23 middle school or YA (shown with a %)

- 11/23 published in 2023/24

Top five from this batch

- Maggie Stiefvater, The Scorpio Races

- Catherine Chidgey, Remote Sympathy

- Paul Lynch, Prophet Song

- Kathryn Scanlan, Kick the Latch

- Max Porter, Shy

I realised copying my reviews over from Goodreads that I'm seemingly unfailingly enthusiastic about everything I read. I actually discard about a third of the books I start; if it's not working for me I stop. The book about George Eliot below is the only exception in this period where I really stuck it out (and am glad I did)

% Maggie Stiefvater, Scorpio Races, 2011

Read because: I was re-reading horse-themed books to go alongside Rachael King's The Grimmelings.

I continue to adore this book. Puck Conolly and her two brothers are recently, rawly orphaned, left together in their island home. They're struggling to keep the edges together, and Puck sees the solution the in the chance of winning the island's annual Scorpio races: the deadly autumn beachside race, where the men of the island compete on the otherworldly capaill uisce, the waterhorses dragged forth from the sea, for pride and for livelihoods.

Absolutely terrific incorporation of a mythical element in the fierce, unpredictable waterhorses, into an entirely human setting. Puck, with her strained relationship with her older brother and loving worriedness for her younger, is totally believable. There's a love interest who's more than a love interest and one of the best-depicted villains I can think of. So good.

Charlotte Wood, Stone Yard Devotional, 2023Read because: Wood is one of those authors I read on trust any time a book comes out.

One for the nun file! A woman walks away from her workplace and relationship, returning to her small home town on the Monaro plains and joining a devotional community of women in the midst of two plagues - the Covid epidemic and raging torrent of mice. Quiet, controlled, thoughtful.

% Elyne Mitchell, The Silver Brumby, 1958Read because: horse-themed reading, as above. And a book that holds a deep (but indistinctly remembered) place in my childhood reading.

This bestselling series originated when Elyne Mitchell - author of adult non-fiction and mother of four on a rural property in northern NSW - started typing up a story for one of her daughters who was bored by the books the Correspondence School offered.

I hoovered these books up from the New Plymouth library when I was a kid. They fall firmly into the noble animal genre. The storytelling is quite simple; it literally opens on a dark and stormy night when a pale foal is born on a mountainside and named Throwa.

Throwa grows up, taught to be canny and watchful and avoid men who will hunt him for his beautiful colouring. The book tracks his ascendancy - from watching his own father Yarraman fight off and eventually lose to The Brolga in the competition for domination of herd and habitat, to his own eventual battles with and defeat of The Brolga - alongside his continual effort to stay free of the traps of men.

It’s not great writing or characterisation. It’s really no

Watership Down. But it had the solid familiarity of childhood and I can still see why I loved them.

Max Porter, Shy, 2023Read because: although I've come to Porter a bit late, I'm catching up. Shy is intense, lyrical, deeply sad; as tender as Lanny but in a differently spiky way.

Rebecca Yarros, Fourth Wing, 2023

Read because: I was keen to see what all the romantasy hype was about.

It’s a tale as old as time - or at least contemporary fantasy writing

A magical school. Complex family lineages and relationships. Hot young people. Misapprehensions and long-held assumptions. Passionate hatred between main characters based on historical circumstances. Dawning awareness. Struggle between what they’re been taught and what they see now. Much smouldering. They have quills to write with but also the concept of toxic men. Two bouts of “explosive sex”. A finale where truth is revealed, love is dashed, and a sequel is set up. I’m not at all surprised it’s been wildly successful but I am puzzled that it’s being viewed as something new (although I'm not qualified to speak on how distinctive the disability representation is in this genre).

Molly Keane, Good Behaviour, 1981

Read because: I *think* Keane was mentioned in the credits for Stone Yard Devotional.

Good Behaviour has an opening with echoes of O Caledonia, as middle-aged spinster Aroon St Charles terrorises her unloving mother to death with an indigestible rabbit mousse. From this startling opening we travel back through Aron’s child and young woman-hood at Temple Alice, an Anglo-Irish manor where her family lives in rapidly fading glory.

Keane’s achievement is to construct a narrator who sees all, but understands hardly anything, turning the reader (as her editor Diana Athill describes it) into a story-watcher. It’s a wicked story, full of snobbery, small cruelties and withheld affections. The trick is to make it engrossing, and Keane’s writing is endlessly quotable (an upset elderly man - “He looked like an angry blue-eyed baby with a pain it can’t explain”).

% Kate DiCamillo, The Magician's Elephant, 2009

Read because: it was lent to me by a young friend. And I'm back-reading DiCamillo this year,

Not my favourite of her books. And yet, still so beautifully done. In another writer’s hands this story of an orphaned boy finding his sister could be saccharine but here it is profound, and moving. It’s the care and compassion DiCamillo takes for each of her characters, right down to the blind dog Iddo, that makes a story of finding the right path so perfect, that leaves your heart grateful such compassion exists in the world

Paul Lynch, Prophet's Song, 2023Read because: last year's Booker Prize winner.

I can’t remember the last time a book has me reading with my heart in my throat like this, stomach hollowed out by the final helpless, horrifying sections.

Set in Dublin after a totalitarian regime comes to power, the story starts with two members of Ireland’s new secret police coming to Eilish Stack’s door at night, asking for her husband, union organiser Larry.

Larry is taken in and never released, and Ireland begins, fast and bewildering and filled with threat, to crumble around Eilish, her four children, her job, and her father who she is also trying to care for through his increasing dementia and the rapidly mounting fear and control.

Lynch writes the whole book in a propulsive, speeding, anxiety-inducing present tense that deserves the trope “sweeps you along”, you’re powerless in its grip:

Bailey is watching the protest in a phone and she sees their image giant and alive and can sense her fear has become its opposite, wanting now to surrender to this, to become one with the larger body, the single breath, feeling her might grow in the triumph of the crowd. For an instant she is met with some inchoate feeling of death, of victory and slaughter in vast numbers, of history laid under the feet of the vanquisher and she stands as though with some great blade in her hand, she brings the blade down and shivers with exaltation then takes a sharp breath, two gardaí are walking among them with cameras recording faces despite booing and jeering from the crowd.

Zadie Smith, The Fraud, 2023

Read because: another of the big books of 2023.

Loved the first third, then got bogged down. Possibly because I was reading the searing “Prophet Song” at the same time. Would actually love to read this while visiting London, feeling the city around me.

% Katherine Rundell, Impossible Creatures, 2023

Read because: Pretty much the English-language middle-grade book of the year.

Am I a griper for not feeling like the characters were terrifically well-drawn, compared to the bestiary of fabulous creatures?

Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping, 1980

Read because: hmmmm. Maybe I just spotted it on the library shelf?

A small town, small-format saga revolving around sisters Lucille and Ruthie, whose upbringing passes from their competent widowed grandmother to their avoidant great-aunts to their drifter aunt Sylvie, all in a mildewing home in Fingerbone, a tiny town set on a glacial lake.

Left to drift and meander, Lucille decisively opts out of the much-reduced family and into a conventional life, while Ruthie drifts into her aunt’s transient way of being.

A gentle, rolling, observant book where sadness is simply part of being alive, and judgment is reserved throughout.

% Kate DiCamillo, Raymie Nightingale, 2016

Read because: Also lent to me by a young friend.

It’s the 5th of June 1975 in Lister, Florida, and two days ago 10 year-old Raymie Clarke’s father ran off with the local dental hygienist, Lee Ann Dickerson. But Raymie has a plan to make him come home, and it just hinges on winning that year’s Little Miss Central Florida Tire pageant.

That’s why Raymie is standing in the hot noonday sun outside baton-instructor Ida Nees’ house, waiting for her lesson to begin, with two other girls — Louisiana Elefante, orphaned daughter of two trapeze artistes, and Beverly Trapinski, tough-as-nails and worldly due to her dad’s job as a cop, only he’s in New York and she’s not.

Kate DiCamillo just has a gift for getting straight under your skin.

Raymie Nightingale is less fantastical than her more fable-like works, but the mixture of sadness, bravery, owning up to life and hope all run straight through this book too. I loved it.

Read because: Booker Prize shortlister

A circling story of grief, identity and memory. Marianne’s mother disappears when she is eight, leaving behind her gentle husband Edward, newborn baby Joe, the besotted Marianne and their rambling home in a small English cottage. In overlapping slices of narrative, Marianne moves between the child, teenage, early adult and young mother stages of her own life, seeking to understand her mother, how her mother has shaped her own self, and inheritances of story, belief and madness that submerge and re-surface over time.

Some parts of this first novel feel underbaked - especially a section about therapy and inherited trauma. In large parts though it is a gentle, sad, believable story of people doing their best to live on after an unbelievable breakage:

Life after she left divided into things you could fix, and things you could not fix. My hair, for example, was fixable. At first I didn’t understand why it was rough, and brownish, and stuck to my face. Why the brush didn’t help. Then I got nuts, and Edward learned about tea tree shampoo and plaits and we found hair was a fixable thing.

Some things could not be fixed. Shock-induced type 2 diabetes. Chronic eczema. The plates I dropped. The chewed-up home-made jumpers that we shrank in the wash. The kitchen garden. The air in the kitchen: the way the air in the kitchen set like jelly, and you had to be brave to walk into it, leave the radio in very loud, or open the door to the living room and leave children’s programmes running on a loop to break up the jelly into moveable chunks you could walk through. The way the edge of everything was muffled, soggy, incomprehensible, distant. The distance never really went away.

Lorrie Moore, I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home, 2023

Read because: It's Moore's latest

Finn’s brother Max is dying of cancer in a hospice in the Bronx and while visiting him, Finn discovers his estranged girlfriend Lily has finally succeeded in committing suicide. Buried swiftly in a green cemetery, when Finn goes to find Lily’s grave her zombie corpse appears, and the two embark on a zombie rom-com road-trip to relocate her to a forensic science body farm, and dig over the failings of their relationship. This 21st century story is interspersed with diary entries by a woman named Elizabeth, the last landlady of an aging dandy who is very likely Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

This could be funny, or touching, or spooky, and it’s not any of those. It’s a lot of incredible writing that feels in search of a plot that does something. The zombie character line reminded me a lot of American God’s Laura Moon — resentfully loved, the bodily decay mimicking the Eurydice theme of inevitable loss. The sections narrated by Elizabeth suggest a book I’d love to read — but not this one.

The writing though!!

Someone at the pots and pans store was speaking of a neighbor woman who had become a bitter old recluse and I piped up that that was going to be my own fate and no one kindly took it upon themselves to disabuse me. Everyone simply stared in bright-eyed agreement. I fear they have seen me muttering to myself on the street. Once, I swaddled a burn on my arm with a dressing and then when I was out walking I began to swat at it, thinking it was a large moth that had wrapped itself around me. I should wear a duster and one of those new pancake hats that are all the rage. I should take up ornamental farming with guano.

Catherine Chidgey, Remote Sympathy, 2020

Reading Catherine Chidgey’s books backwards is like meeting someone at a fun dinner party then finding out their tragic backstory.

The Axeman’s Carnival and Pet - my first Chidgey experiences - both have some brutality and fear mixed into them, and are also undergirded by invisible research. Carnival though has the security (for me) of rural New Zealand and character types I recognise from childhood; Pet has its boiled lolly sheen and safety blanket of suburban 1980s iconography.

Seeing that characterisation and research detail applied to Nazi Germany then, first in The Wish Child and then in Remote Sympathy, is startling and unsettling. Can anyone avoid feeling like a voyeur reading the pain and horror of this period of history?

Self-deception reigns in Remote Sympathy - the interwoven narratives of Buchenwald’s chief administrator Dietrich Hahn, his wife Greta, and prisoner Dr Lenard Weber. Each viewpoint is time-stamped.

Dietrich’s words are taken from a 1954 interview transcript, suggesting he has survived the post-war trials, and throughout his passages he seeks to justify his choices and behaviour.

Weber’s words are presented as letters written to his daughter in 1946, telling us he survives the camp.

Greta’s story is told as an “imaginary diary”, and hers is the real-time story - there is no guarantee of her future, and at the same time she is the character with the most cloistered view, trying hardest not to see the horror supporting her family’s comfortable life on the edge of the camp.

A Greek chorus, the “private reflections of one thousand citizens of Weimar”, puts the reader in the position of the accepting bystander, the community who twitches their curtains closed and averts their eyes to preserve their ability to deny the ash in the air, the emaciated factory “workers” in their streets.

The word the book has left me with is “restrained”. By removing the question of survival, Chidgey can immerse us in the detail and the psychological states of her narrators. As a reader, you do yourself experience the remote sympathy of the title — Chidgey is fantastically controlled. I read the book in the wake of hearing many reviews (but not yet seeing myself) the movie The Zone of Interest, and I kept thinking while reading about the focus on sound design in the movie — sound being the link between again, safe family life on the edge of a concentration camp, and the stories of hope and denial people simultaneously tell themselves to make it through the day.

Lauren Groff, The Vaster Wilds, 2023

Read because: Groff's Matrix is one of my most favourite books of the last 5 years.

I didn't love this, because it's not Matrix. Having said that, after hearing Groff speak last month, I now what to re-read it and review my opinion (which isn't an opinion, actually, it's feelings).

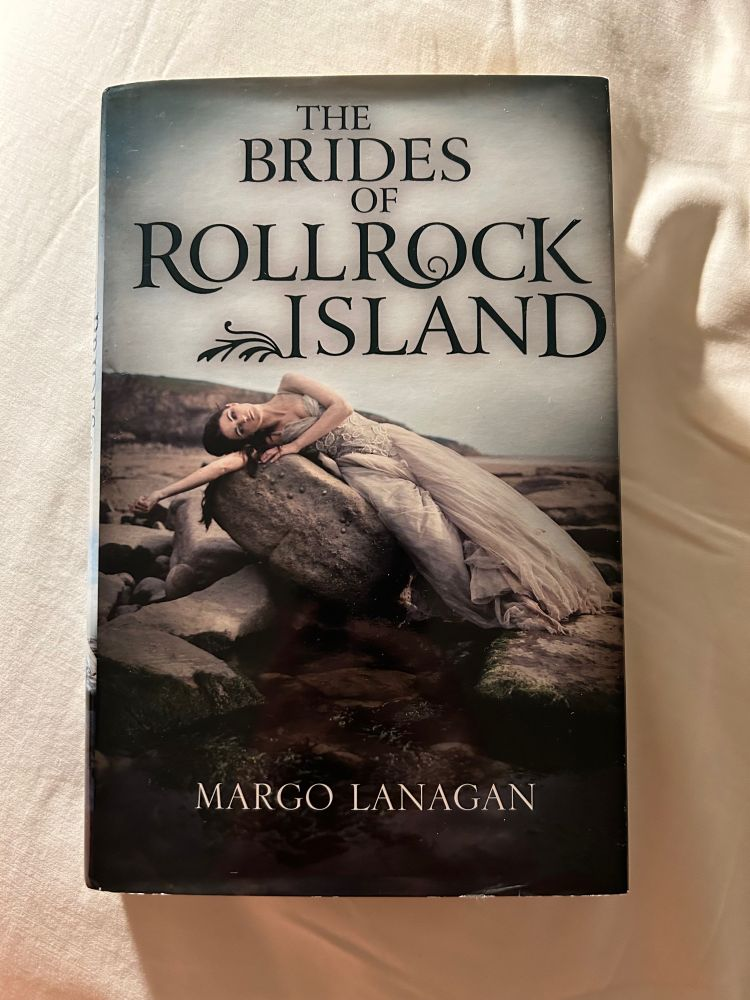

% Margo Lanagan, The Brides of Rockroll Island, 2012

I’ve been sleeping in this book since 2012, when it came out. I adore Lanagan’s writing and was excited for this, but after my husband died that year I stopped being able to read for months. This was one of the books I tried and failed on in that period, and it’s sat on my shelf ever since.

I finally picked it up again, and it was as good as I hoped it would be, back when.

Lanagan’s dark folklore and willingness to let women’s sexual power be complex both shine here.

Rollrock Island is small, hardscrabble, inhabited by fishing families and one pub. It is also home to many seals, and magic. At the start of the book a young girl, Misskaella, finds herself increasingly drawn to the seals and a sense of power emanating between them and her. The old people of the island begin to acknowledge the power she holds: a witching power, an ability to draw forth from the female selfies beautiful young women — innocent, compliant, dark-eyed, slim-limbed, irresistible to the men of the island.

Misskaella extracts a terrible price for this service, as men approach her covertly to secure them a seal bride: a cash price, ruinous to their families, but also a price that destroys relationships and families. In a generation, all the women have left Rollrock to the men and their selkie brides, and the sons they give birth to.

Misskaella is not to blame for the men’s pull to these women, but she is also not faultless in her heartless feeding of their desire. The men and the boys live in a dream with their intoxicating, compliant women — but it cannot last forever.

The most arresting parts of the books are narrated from the perspective of childhood Misskaella, and young Daniel Mallett, the son of a Rollrock man and seal bride. The language is rich and dancing, lulling and yet deceptively strong, like a beach on a dark night. Lanagan’s ability to create and convey an environment— natural, physical, emotional - is wonderful. I’m so glad I finally made it here.

% Kate DiCamillo, Louisiana's Way Home, 2018

Read because: Working my way through the back catalogue

DiCamillo’s warm, confiding, trustworthy tone is a balm, but perhaps you can read too many of her books too closely together & have the magic wane a little as a consequence.

Kathryn Scanlan, Kick the Latch, 2022

Read because: Maybe the paperback has come out, and I picked it up from a NYT review? All the smart people read it in 2022, I just missed it then.

Such an unassuming book but utterly riveting.

Scanlan conducted interviews with Sonia, a career horse trainer, over several years and then distilled those down into 120 pages of vignettes, dots that link from the day of Sonia’s birth —

“I was born October 1st, 1962. I was born in Dixon City, Iowa. I was born with a dislocated hip. The doctor said I’d never walk. My mom said, Oh no, there’s got to be something. So they put me in solid plaster from my chest down, with just a little space for my mom to put on a diaper. I was there five months. Then I went to two casts with a bar between with these special shoes. Ended up I could walk. I attribute that to Dr. Johnson. My mom always said, We’ll, if it wasn’t for Dr. Johnson.”

— through her falling in love with horses as a child, talking herself into her first jobs as a teen, her career moving around North American stables and race tracks, and then to her late middle-age, retired, settled, reflective —

“By the time you’re my age, you’ve had a lot of injuries. And where there’s injuries, you get arthritis. I got buggered up a few times but I thought I escaped pretty chops. Now I wake up on a rainy day and think, I remember this. I remember it right here.”

It’s a story of “grooms, jockeys, racing secretaries, stewards, pony people, hot walkers, everybody.” There’s kindness and brutality, friendship and exploitation. The voice of Sonia, as conveyed by Scanlan, is clear as water, amazingly without grievance. Her life could be frothed up into a 600 page Barbara Kingsolver-style epic, but Scanlan slides it into the world as a scant 120 pages that are engrossing, intimate, surprising. So good.

% Judy Blume, Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret, 1970

Read because: I was given a copy of this book by friends for my birthday, and we watched the movie adaptation together. We shared a similar experience of being unsure if we had actually read the book as children, or had picked up its classic motifs (“I must, I must, I must increase my bust!”, the anxiety of being the last in a group of friends to get her period) by osmosis.

We all knew this was the book that was about getting your period. But it had also completely bypassed us that it was a book about religion — a much larger proportion is given over to Margaret’s quest to figure out what god she could believe in, as the daughter of a Christian mother who was ostracized by her family for marrying her Jewish dad. Margaret’s parents both stop practicing themselves and tell Margaret she can choose her religion when she grows up.

I’m not sure how much has changed between the 1970 original and the version I read this weekend (we all remembered sanitary pad belts as a massive feature of the book but it appears in the 80s these got changed to stick-on pads). Race does not feature in the book, and sexual politics hardly at all — the only ick factor is the way a young new teacher is positioned as being drawn too the “developed” girl in Margaret’s class (although this is delivered as an insecure friend’s analysis, and like Margaret, we come to doubt her credibility).

It remains a thoroughly charming, confiding book with huge warmth and respect for young women and a totally memorable (even if you don’t actually remember her) Margaret.

From a NYT review:

“To us, Margaret Simon wasn’t a character, she was a proxy — for the girl who stuffed socks in her bra, who felt uncomfortable in her own skin; for the girl who was homesick for a friend who had matured overnight or moved away or turned mean; for the girl who struggled to make sense of the diagrams on the origami-folded instructions inside the tampon box.”

Emma Donoghue, Learned by Heart, 2023

Read because: I read everything Donoghue puts out.

In the privacy of my skull, I remember every minute. How I caught love like a cold, at fourteen; or you did, and passed it on to me; how it flared between us. How we slept, rose, learned, played, ate, inseparable. I couldn't tell my own pulse from yours. We spilled ourselves like ink.

Emma Donoghue's latest book is based on a true, and terribly sad, story, and a great deal of academic and community research that revolves around the figure of Anne Lister(1791-1840), the famous diarist, dubbed "the first modern lesbian". It's the lesser known figure of Eliza Raine (1791-1860), whose history "is full of gaps and puzzles" as Donoghue says in her author's note, who provides of narration and perspective in this Regency-era boarding-school love story.

Raine was one of two sisters born in Madras (now Chennai), to an English father who was a head surgeon for the East India Company, and an Indian mother who lived with Raine for at least a dozen years, although nothing is recorded of her: name, age, family, ethnicity, religion ...

Both the Raine girls were baptised, and in 1797 at the ages of eight (Jane, the older sister) and six (Eliza) were sent on the long sea voyage to England. Their father set out to follow them in 1800 and died on the voyage; his estate recorded payments to "Dr Raine's woman" in Madras, but these were only made for two years. Jane and Eliza were left with a respectable inheritance of four thousand pounds each, to be payable when they married or reached the age of 21.

Eliza and Jane moved into the care of the Duffin family in York, and by 1805 Eliza was boarding at Miss Hargreaves' Manor School in York, an "antique hodgepodge" of buildings, where she is one of seven girls in her year. The book opens with the fine detailing and imagining of a boarding school for young ladies at this time; the endless rules and elaborate system of merit and demerit points that enforce them; the cold rooms, plain clothes, restricted food, all designed to build character; the complex relationships between the girls of her year, and Eliza herself, achingly aware that with her illegitimate status and biracial existence:

Pupils are allowed a single flounce at the hem, or a silk shawl instead of cotton, without getting a vanity mark, but Eliza doesn't risk it. It gives her secret gratification to confound expectations. Restraint in dress is not a virtue looked for in the little Nabobina, as she heard Betty Foster call her under her breath, that first week. Their classmates seem disappointed by the Raines' lack of splendour - no decorated palms, thumb-rings the size of walnuts, ropes of pearls, belled ankles, or gold nose-jewels.

Eliza practises her gleaming smile in the speckled looking-glass. The well-mannered call her complexion foreign-looking or tawny; the insolent, swarthy, dusky, dingy or plain brown. She reminds herself her skin is clear, her features generally thought pleasing.

Into this restrictive and restricted environment erupts Anne Lister: boyish, outrageous, knife-sharp, masking her vulnerability with acid humour. The girls circle her like another exotic, entranced and repelled, but it is Eliza she is assigned to share a room with -a tiny garret room they christen the "Slope". The girls grow closer and closer and closer, and then their emotional connection ignites as a physical relationship.

Lister leaves the school after about nine months, to Eliza's heartbreak.

The chapters set in the school are interspersed with imagined letter written to Lister from Eliza in 1815. Lister and Eliza stayed intimately connected for some years after school, but Lister eventually moved on to other loves, leaving Eliza drifting and heartsore. It appears her mental health and behaviour deteriorated, to the point where she was put in an asylum in York - within walking distance of the school they had attended. She would spend the rest of her life either in asylums, or the care of people her family members assigned her to, alone.

Some reviews I've read admire the book a lot, but wish Donoghue had sped through some of the boarding school details to get to Eliza and Lister's thrilling discovery of the pleasures of love faster. I dunno. I got a lot of pleasurable flashbacks to A Little Princess reading this - the deeply imagined boarding school environment that as a reader you can sink yourself thoroughly into. Learned by Heart has the secretive, doomed love intensity of Romeo & Juliet, with the warring families replaced by Eliza's biracial background and insecure social standing, uncomfortably ensconced in one country and ever further away from the gauzy memories of her birthplace.

Donoghue excels at emotionally acute stories told within tight parameters, and she puts them out at a startlingly rate, given the range of historical periods she's moving through (a monastery in 7th century Ireland and a hospital in 1918 Dublin in the latest two). I really, really enjoyed this.

Muriel Spark, Loitering with Intent, 1970

Read because: It's been sitting on the shelf for ages, and Molly Keane (above) made me think of it.

I'm quite flummoxed by this book, I struggle to describe what's going on in it. It has Sparks' inimitable inhabitation of a young woman's mind, but the plotting (which is all about - plotting) is off the hook. Sparks is running rings around the reader and it's a hell of a lot of fun.

Claire Keegan, So Late in the Day: Stories of Women and Men, 2022

Read because: Who doesn't read all of Keegan's books? However, I didn't get swept away by this particular collection.