As they say - this is a long post that I didn't take the time to make short. It meanders through a group of musings about career progression, with a long digression into Brazilian jiu jitsu. It's an effort to get these ideas out of my head, and back into the habit of sharing.

* * *

A few weeks ago I attended the CAM-D (Council of Australasian Museum Directors) and AMAGA (Australian Museums and Art Galleries Association) meetings in Perth.

I'd been nervous about going to CAM-D. This group is made up of the leaders of the state and national museums in Australia and Aotearoa. Because the pandemic struck when I was just 3 months into my role at Te Papa, I had only met a few of them face to face before becoming Tumu Whakarae.

For nearly two and a half years then, I've been joining Zoom hui with this group, always feeling a bit of of my depth. These are really seasoned professionals. Most have at least one, sometimes two (possibly three) decades of experience on me. My nerves about joining then were exacerbated by losing my bag on the flight to Perth, meaning I'd had to do an emergency shop to get clothes for the first gathering. At least that gave me a topic for small talk.

As it turned out, of course, everything was fine. No-one treated me like the little kid who didn't belong at the grown-ups' table (that's my internal narrative playing out, and it's also running out: I'm 42 now, rapidly moving past even "youth-adjacent"). It was magical to spend time with a group of people used to working and thinking and managing at significant scale in my sector. We had shared challenges, and many shared aspirations. We're balancing similar tensions, and competing priorities. I felt surprisingly at home very quickly.

AMAGA was completely different. Hundreds of people, compared to about a dozen. A council and organising committee that favours younger / newer professionals in the sector. And an explicit activist spirit, one that is very familiar to me from earlier in my career but not a space I occupy much now: of kicking against accepted practice and pace of change.

The conference was strongly flavoured by emerging museum professionals (a loose definition would be "people in their first ten years of museum practice"), and the strengths of these regional and national EMP networks was obvious. Listening to their presentations and talking to people between sessions, I found myself feeling my age in a really specific way, which I spend a lot of time thinking about. At 42, generationally I sit right on the cusp of Gen X and Millennial. I often feel like I'm in the middle, holding hands between the Boomers and Millennials - able to see both sets of perspectives and life experiences, not feeling settled in either camp.

Which led me to tweet this during one of the talks:

I’m old enough now that every time I hear the phrase “emerging museum professionals” I start thinking about what we should be doing to support submerging museum professionals #amaga2022

— Courtney Johnston (@auchmill) June 15, 2022

I've got to hat-tip to Megan Dunn for the "submerging" bit, which she coined in this 2013 essay for the Pantograph Punch. Megan there is talking about the flip side to the emerging artist, who is taking off on a career trajectory: the submerging artist, who slid off the ladder of career progression.

When I was a baby PR at City Gallery Wellington - my first full-time job - one of the things I had to do was write media releases. One of the clichés that gets rolled out high up in these releases is the status of the artist. It looks something like this:

- Emerging

- Rising talent

- Mid-career (the trickiest)

- Established

- Senior

- Renowned

This is reductive, of course. There are those artists who emerge later in life; those who were overlooked for chunks of their lives; those whose work or impact wasn't recognised within the mainstream gallery system but were fully formed outside it. But the key to it is that the only way is up. There's no resting spots, no plateau, no in & out flow. And there's definitely no wind-down.

Te Papa employs approximately 600 people. A percentage of these are long-standing professionals (across a range of practices) who are coming to the end of their full-time or paid working lives. The negotiation of the final period of your working life inside a museum is, I think, worthy of as much attention and support as that emerging / entry period. And yet it is something that is rarely discussed out loud. How to accommodate, enjoy the benefit of, and celebrate people who are late in their careers, who are going through family changes, health changes, financial changes, and for some a massive change in their identity, as they contemplate leaving a career (and sometimes a single institution) to which they have dedicated decades' of mental, physical and emotional energy. Not to mention the subtle (or unsubtle) pressure of the generations behind these people, who - frankly - want the jobs they currently hold. While there's a lot of emphasis on internships, promotion and career development, there aren't similarly strong shared frameworks in place for how to reduce working hours, responsibilities, or shift the emphasis from producing outputs to transferring knowledge.

That's what I actually meant by "submerging" in that tweet, rather than the people who have trialled a museum career and decided it's not for them (that was me, by the way - I left City Gallery vowing I would never work in a gallery, and look how that worked out). Or, to put another spin on 'submerging', the people who feel like they are stalling in their career.

We tend to think of careers as ladders, patterns of progressions. One speaker at AMAGA suggested that they should be thought of more as jungle gyms, where you might move laterally as well as vertically. New Zealand has a government careers website, which lists a wide variety of models.

I've not got the insight to propose a different model. And I'm not sure I want to promote a bell curve theory, from emerging to peaking to submerging again on the other side. Or a seasonal one, moving through Spring to Winter. What I want to explore is more the micro-phases within your career journey, that play out repeatedly as you take on new roles, or new life experiences alongside your working life. And I'm thinking a lot in sporting analogies.

This year, I've gone back to jiu jitsu. I've been training since August 2012, but I took a long patch off over the past two years; a combination of lock-downs & Covid restrictions, a bad ganglion cyst, and also just feeling overwhelmed in my new job and not having mental space for a sport that is literally all about being up in someone's face.

BJJ has a belt system: white, blue, purple, brown, black. While there is a syllabus, every club interprets this differently, and awards belts differently. But let's say, roughly, that each belt represents 2-3 years of solid training, skill acquisition, and a certain kind of commitment to your club and the people you train with.

I'm a brown belt. But I love going to beginners classes. I like to help out, supporting new people, especially women. It's also soothing, running through basic techniques that you know well. And as with most disciplines, you find yourself learning so much more about what you already know through teaching it to a diverse range of people.

So one night recently I was paired up with a fairly on-to-it newbie, a smaller dude who could listen to the instructions and to me. And next to me on the mat was a pair of the most exemplary munters. Fresh off the street, muscular dudes who quite likely watch UFC in the weekends and listen to the Joe Rogan podcast.

It's important for context that you know that everything you do in BJJ is done with a partner. There are no kata, like karate. From your very first class you are paired up with another person, doing something that looks like full-body, floor-based peaknuckle. People either love the intimacy and the intensity of being thrown into such close physical proximity with a stranger (or even worse, your mate who came along with you, and now has his face planted in your groin area because your first class happened to be triangles) or it freaks them out and they never come back. To begin with, it can feel a lot like being assaulted. You have no idea what's going on, and another person is trying to hurt you.

So, these guys were just a picture to behold. Rigid as fuck, because they were so uncomfortable being wrapped in each others' arms. Hyper-aroused, flooded with fight-or-flight chemicals, they could hardly hear the instructor because of all the brain chemicals rushing around. Because they've learned that strength is a virtue, every move was being performed at 200%, which meant nothing worked properly. BJJ is full of weird specific movements and you get taught them piecemeal, so these guys had no context in which to place the particular technique they were being taught. And they were so self-conscious that when other people tried to help them, they either couldn't hear the advice, or had all their barriers up against being told how to do something better.

And watching them, I realised that this was the exact parallel of my first two years as a CE. So hyper-aware of being watched I couldn't remember what it felt like to do something naturally. Loads of advice coming in, but no existing experience to place it into context. The rushing white noise of expectation and fear of failure in my ears. And the crushing experience of simply being very, very bad at something and having to be okay with doing it poorly for as long as it took to learn how to do it well.

The thing with jiu jitsu is that it's a lot like swimming. When you learn to swim, you start from the point of drowning. Learning to swim is the process of getting better and better at not drowning, until magically, you're swimming, not drowning, when you take your feet off the ground. Then you learn to take breaths, to experiment with different strokes, to dive under water, to turn flips. You can't remember what it felt like to not be able to swim. You also can't - without quite a bit of reflection and practice - effectively coach someone else how to transition from not-drowning to swimming.

BJJ's like that. To begin with on the mat you're drowning all the time. Then the moves start to connect together. You learn sweeps and counters and escapes, as well as attacks. You learn that if they do a, it's likely heading towards b, and so you can prep to do c, and if c is unsuccessful, you can transition to d - in fact, maybe you'll feint d in order to pull off an e. You learn to breathe through pressure. You distinguish pain from actual threat of injury. And once you've got some experience and perspective, a body of knowledge, some resilience, you might even graduate to self-awareness: an insight into the impact your actions have on your partner, how you can be a helpful training partner by considering their needs as well as your own, how you can pace the speed or intensity of a roll to bring out the best in an encounter for both of you.

This year, I feel like I graduated from white belt as a CE. I reckon most days, I'm hitting purple. Enough experience to see the patterns playing out, to draw on a decent repertoire of techniques, predict outcomes, and be conscious of the people around me. Some days I find myself acting like a white belt and its crucifying, but only because it hurts my ego. What I need to remember though (and this is easy for me, because I am lucky to have a really strong natural growth mindset) is that black belt is still a long way away, and on the way I will have to ride out and push through several plateaus and some complacency. And as my coach says - once you hit black belt, you turn around, and you learn it all again from the basics right up.

That was a long tangent. But what I wanted to illustrate with it is that throughout your career, you're likely to regularly spend time in microcycles, going back to white belt as you take on new responsibilities or roles, and growing through them. I like this way of thinking much more than impostor syndrome (this article has been so influential on me on this topic): you are thrown back into the beginning of a learning cycle, and so logically, things will be harder until they get easier.

So if we think of a career more as a series of looping coils than a straight line tracking up, what might the stages be? Like Tuckman's theory of group development, there might be storming, norming and performing. But there's also the bit after you've gotten to performing - or competence, or mastery - where you plateau. And that's where I think we could spend some time flipping up our mental models.

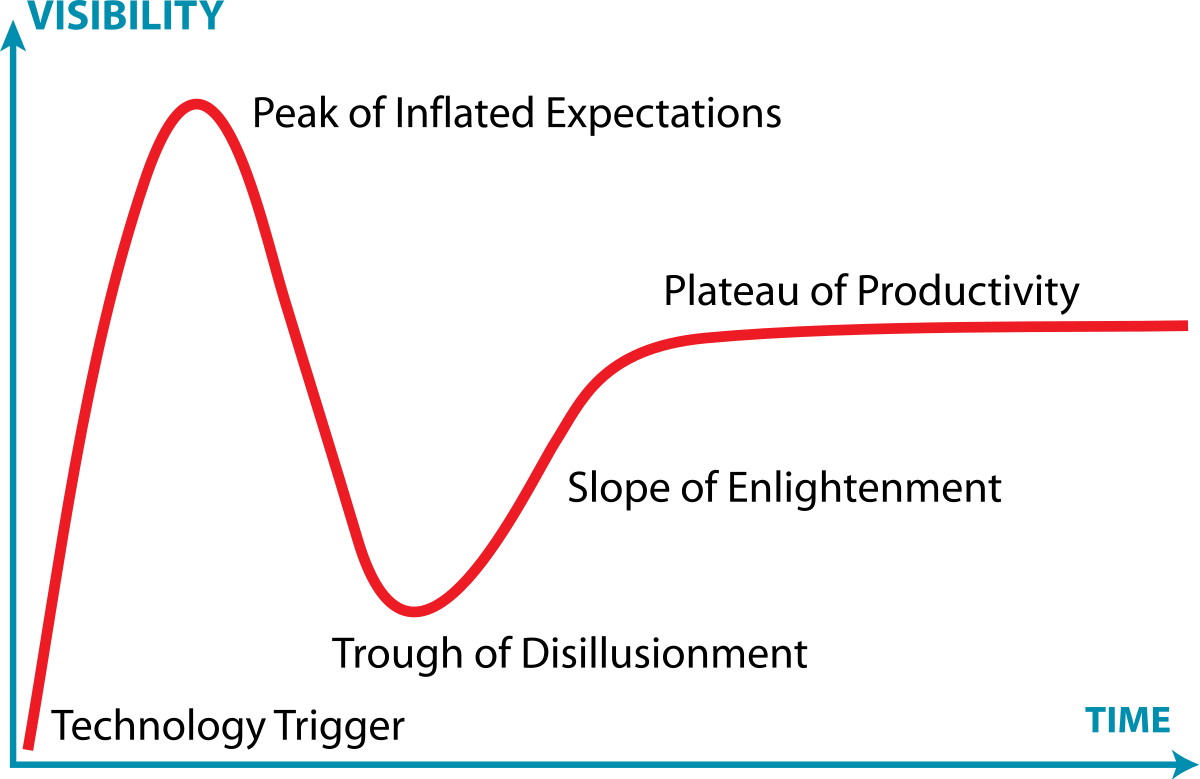

Years ago, I learned about the Gartner Hype Cycle, a theory of the adoption of new technology:

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gartner_hype_cycle |

Let's be honest, we all have peaks and valleys in our careers, times when we hit our stride and do our best work, and times when we're in a slump. Most of us are worried that as we age, our physical and mental skills will decline and we might enter into a permanent slump. And that fear is compounded by the fact that age is seldom seen as an asset in the modern workplace.

I mean the number one myth is that, you know, particularly in certain professions, like, let's just say yours and mine, which is coming up with big ideas and sharing them, that that'll never go into decline. Why? Because it doesn't require, you know, strong biceps, and yet there's overwhelming evidence that in idea professions people experience decline as well. They just don't expect it.

What happens to our cognitive abilities as we age is not straightforward. It actually depends on what kind of mental skills we're talking about. Psychologists have long distinguished between two kinds of intelligence: fluid and crystallized. Fluid intelligence is your raw processing power. It's basically your IQ, your innate capacity for learning and problem solving.... A common refrain in Silicon Valley is that young people are just smarter. When it comes to fluid intelligence, that's generally true. But the story changes with crystallized intelligence, your acquired ability to solve problems by applying your knowledge and experience.

|

| https://www.simplypsychology.org/fluid-crystallized-intelligence.html |