It was strange to walk up Tory Street tonight after work, and realise I won't be bumping into Luit Bieringa anymore, out roaming in his hood.

I have always felt a kind of kinship with Luit (as with Jim Barr) because we all kicked off as young(ish) directors of a regional art gallery. With Luit, it was the Manawatū Art Gallery, which he led from 1971 to 1979. He must have been about 29 or 30 when he took on the role, and oversaw the replacement of a converted house that acted as an art gallery to the purpose-built centre. As he recalled in 2017:

The main thing was to try and change the context in which the gallery operated to becoming a fully-fledged public institution that the community could relate to. We had people's support and if you think of the time, the early 70s, we'd only just moved out of the rugby, racing and beer environment.

I have always loved the Art New Zealand article about the opening of the gallery. I often share it as an example of "guys - they've been doing this for ages". A fundraising team raised about a third of the building costs. Luit "deliberately tried to make the gallery as accessible as possible to all the people of the Manawatu, whether their interest be in functional pottery or conceptual art." At opening, there were looms and a potter's wheel on the ground floor for people to try out; Woollaston, Driver, Albrecht and Wong nearby; a "touch" gallery that people entered blindfolded then felt their way through an array of objects; then upstairs a show by conceptual artist Bruce Barber, including a video work. The original something-for-everyone: hands-on, tradition, new media, recognised quality, defying categories, emerging artists. I always found that inspiring.

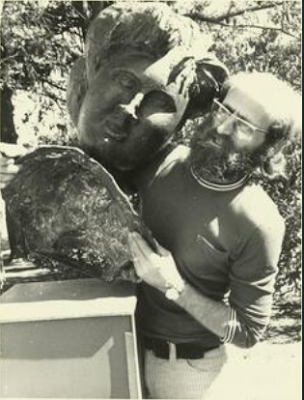

Likewise this beard:

|

| Luit in 1974, from the Manawatu Heritage site |

|

| Cover of The Active Eye, from Te Ara |

|

| Luit outside Shed 11, from a post by Catherine Griffiths |

|

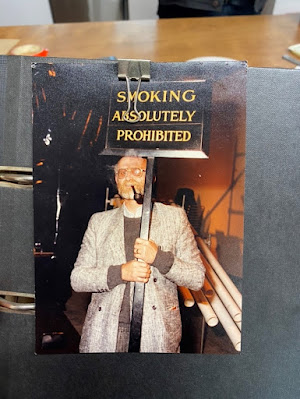

| Photo snapped in Luit's archives last year |

By the time I got to know Luit well, he had repurposed himself as a film-maker, working alongside his wife Jan. They produced documentaries on Ans Westra, the Tovey generation of art education, Peter McLeavey, and most recently Theo Schoon. We were lucky enough to be at the premiere of Signed, Theo Schoon last year, and join Jan and Luit afterwards, with all their friends. Ans was there. Luit bantered at her for not paying attention during his speech. It was wonderful.

Over the past two years I've had a few chances to talk to Luit a bit about his career (not very interested in talking about that) and way of working and making films (much more interested). He loved every aspect of it: the relationships (as exasperating as they might be at times), the arguments, the storytelling, the documentation, the romance of the archive, visual punch, emotional heft, the precious, precious stories of people's lives.

Luit, of course, was a vocal opponent of the dissolving of the National Art Gallery in the creation of Te Papa in the 1990s, and a staunch critic of the way Te Papa has collected, shown and served art since opening. At the same time, he could critique because he showed up; he was a frequent user and annotator of those archives; and a friend and encouragement to staff. He was a critic, because he cared deeply and he had strong opinions. Would that we all had that kind of passion.

Luit Bieringa. He was just a really cool cat. He and Jan have always been incredibly kind to me, first with my first husband, William, and now with Reuben. When I moved to Tory St Luit became part of my neighbourhood, and I'd bump into him often at the lights on the corner or at breakfast at Prefab. This part of Wellington will be quieter without him. While his death does not come as a shock, we all have to get used to this new gap in our environment, that space that will gradually heal over into memory. |

| Jan and Luit in the 1960s, from an Instagram post shared today by Stuart McKenzie |

No comments:

Post a Comment